Certainly one of the most alluring elements of our classical guitar is the rich and varied palette of tones available to us. I remember some years ago standing in the reception line to shake Julian Bream’s hand after his last Boston concert, and one of the other greeters asked him what he prized most in the guitars he played, to which he simply exclaimed – “the sound.” Well, that response can leave one rather at a loss, like, of course; but then knowing what we know about Bream and the beautiful tone color he has given us over the years, and which is captured in his recordings; we know what he meant. That night he

was playing a Hauser I instrument which was simply stunning … some of you may remember.

Volumes can, and have, been written about tone production on the classical guitar, but perhaps we can just scratch the surface a bit here and actually take a peek and one aspect of this, and look at some physical measurement of the sound. The only element we will vary is simply where the string is plucked. We all do this – mostly play just below the soundhole in the “standard” position, move above the fretboard for a sweeter sound, and toward the bridge for a brighter, sharper sound. So in this little experiment we simply pluck the open A string with a gentle rest stroke using the index finger, and we do this in three places – above the 12th fret, just below the soundhole, and very close to the bridge. And as we do this, we capture the waveform on an oscilloscope and look at the frequency components on a spectrum analyzer.

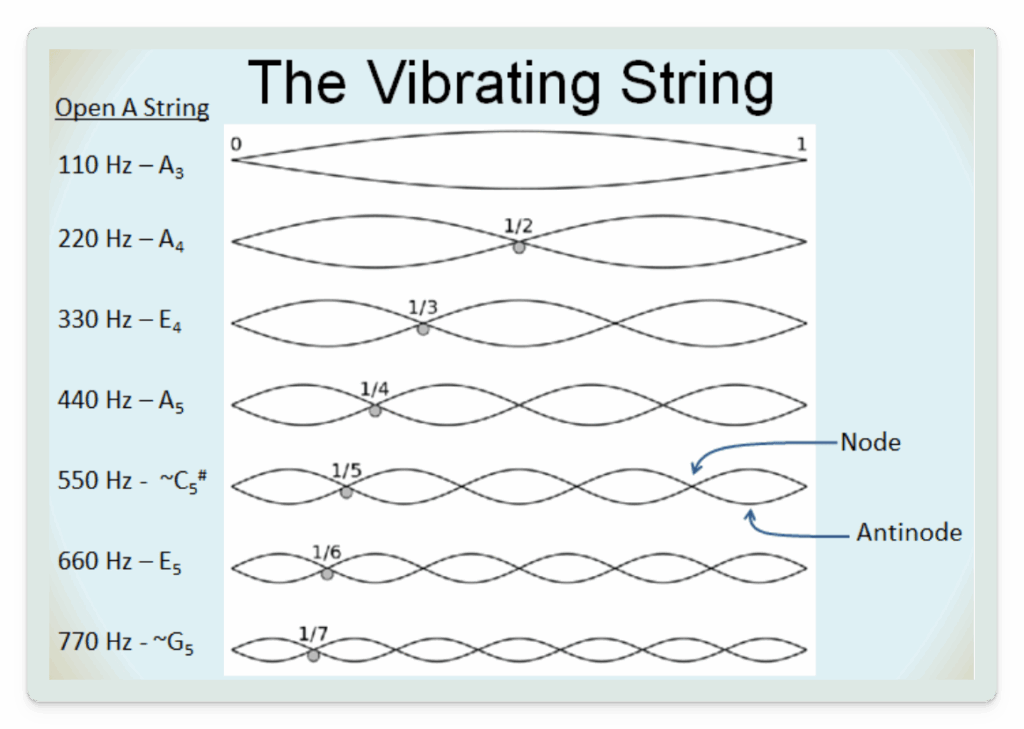

If we were to look at all of the processes which are set in motion when a string is released we would find there are many and with very complex interactions. We can however limit ourselves to a couple of major contributors and glean some useful insights. So let’s first look at what the string will do a few tens of milliseconds after it is released. The string will oscillate in characteristic modes, specifically it will have a fundamental frequency (which will be the specific tuned note), and it will also oscillate at integral multiples of this fundamental which we call harmonic partials. (We can further complicate this by talking about transversal and longitudinal modes, but alas, let’s not do that). Figure one depicts this for the open A (5th) string for the first 7 modes.

Right away we see some very interesting things – we not only get our A (in the 3rd piano octave) at 110Hz, but we also get other higher octave A’s, and an E, and an approximate C#, and an approximate G, and it goes on and on. Now, of course, an E and a C# are the other two notes of the A major chord so it’s comforting to know that these notes are already being given to us by the single string. However, the C# is not quite what we would likely tune our second string to give us on an A chord. Since we typically use even tempered intonation, the C# we would have on our string two, second fret, is likely to be closer to 554 Hz while the C# partial on the A string will be an even 550Hz. You can check this out by playing a C# harmonic on the 5th string just over the 4th fret, and then playing the C# on string two second fret. It will sound slightly out of tune. Now retune string 2 to be perfect with the harmonic from string 5, and then play an A chord second position. The chord will sound very pleasant, but then play an E chord, and uh oh, trouble, which is precisely why it is true that we spend half our time tuning, and the other half playing out of tune.

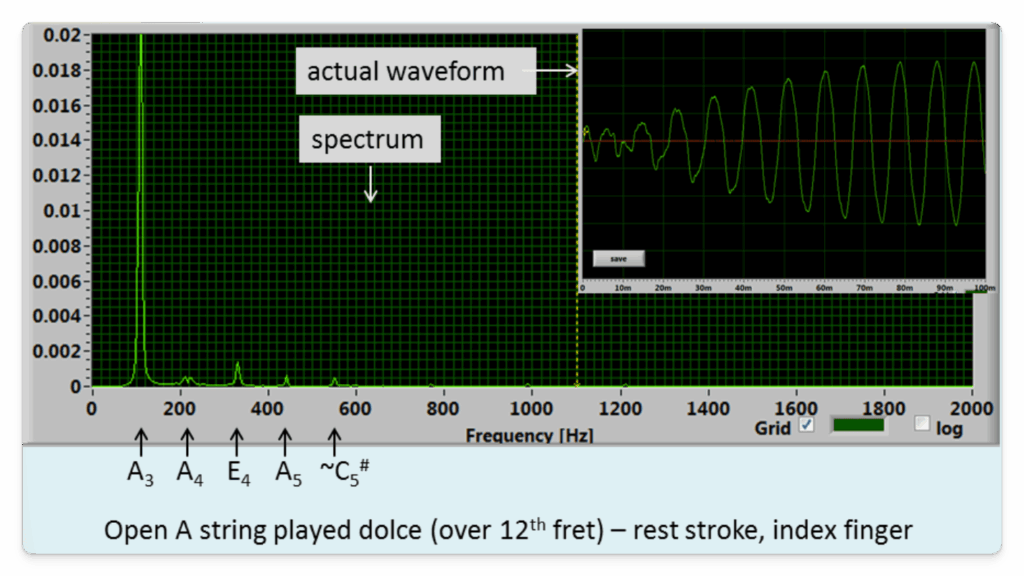

Now let’s look at what we get when we pluck the open A string in the three positions – dolce, standard, and ponticello. Figure 2 is dolce, note in the spectrum that we have the strong fundamental A3 at 110Hz, and very weak components for the other 4 partials – A4, E4, A5, and ~C5#. Looking at the waveform, we see that after the initial transient, the waveform settles down to something resembling a pure sinusoid, as we would get from a tuning fork. The total time window shown is 0.1 seconds, or 100 milliseconds, and it takes about that long for the waveform to reach its maximum amplitude.

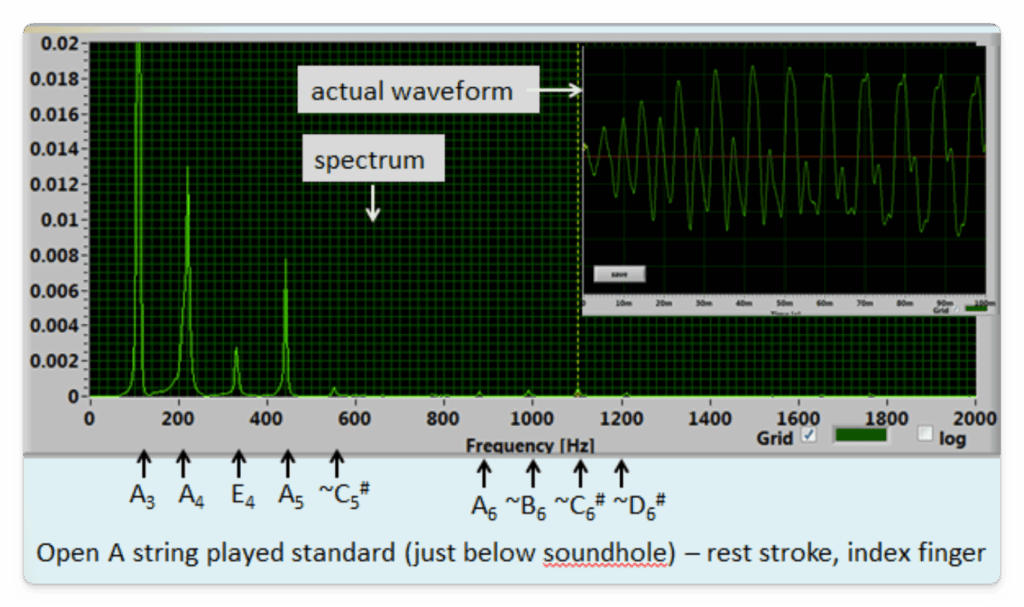

Moving on to the standard position, we see in figure 3 that now the waveform and spectrum has become more complex. Indeed by moving our hand down to this more “fractional” position we excite more of the partials of the string thereby giving us a richer sound. We get strong contributions from A4, E4, A5, and minor contributions from the ~C5#, as well as frequencies which are now close to a B6 and a D6#, the latter being fairly out of tune. Looking at the waveform we see a more complex shape reflecting the summation of all of these other partials, and also we see that the waveform has now risen to its maximum value in only about 40 milliseconds – a faster attack.

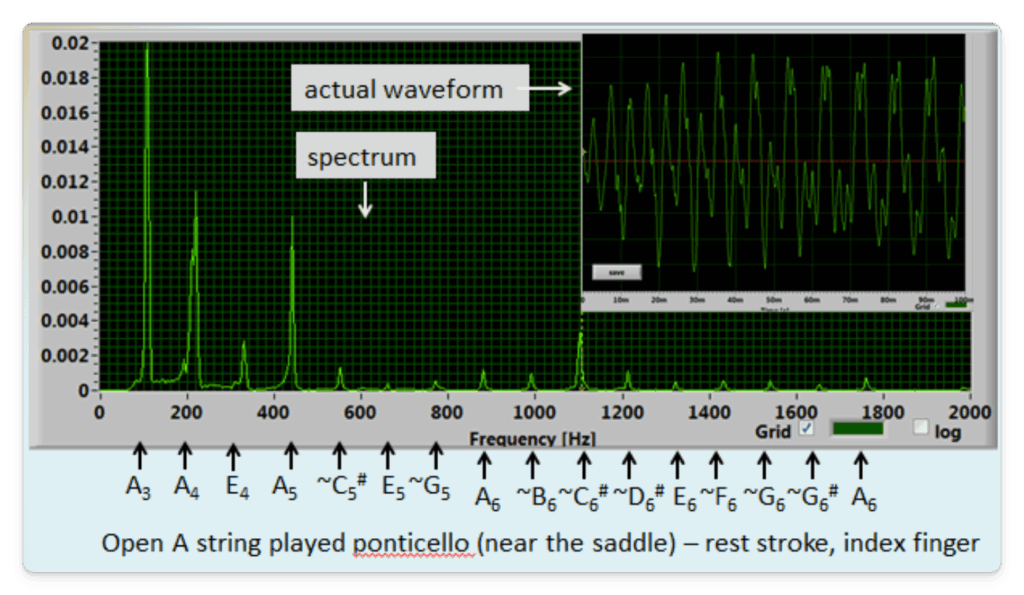

Finally, looking at figure 4, we see the results of playing ponticello. Here a large number of partials contribute to the sound. We see stronger contributions from A5, and many other higher partials. On this particular guitar we get a strong contribution from ~C6# at 1100 Hz. As we go further out in the partials, some of the contributors will be quite out of tune with our even tempered tuning, for example the ~D6# is off from the tuned scale by 34 Hz, and the F6 by 33 Hz. All of this contributes the bright somewhat harsh sound of this playing position. The waveform reflects the complexity of this sound, and again, we notice an increase in the onset transient with near maximum amplitude being reached as low as 25 milliseconds.

So why does this happen? Referring back to Figure 1, the different vibrating modes resolve into standing waves which have peaks (antinodes) and valleys (nodes). When we pluck a string at the location of an antinode, we are putting the launching energy into a location which will favor that oscillating mode (frequency). Now the fundamental and the lower order partials will always have an advantage because it is much easier for the string to have high amplitude at those modes. This is why plucking the middle of the string over the 12th fret so strongly favors the fundamental and overwhelms the partials giving us almost a pure sinusoidal tone. As we move our hand closer to the ends of the string (the bridge being much more convenient than the nut), we start to put the launching energy into the higher partials and move away from the antinodes of the fundamental and 1st partial, giving the higher order partials the opportunity to significantly shape the sound.

There is so much more which contributes to the tone we produce on our guitar – bridge, soundboard, air cavity, back, string, nail shape, use of flesh, which finger is used, angle of attack, apoyando, tirando, and oh yes … skill. It’s interesting to consider that all these factors result in a certain shape of waveform that we perceive as attractive within the given context of the music.